Private sector should join collaborative efforts to resolve problems like water crisis

The severe water crisis in Bengaluru is drawing parallel with Cape Town’s dystopian scenario

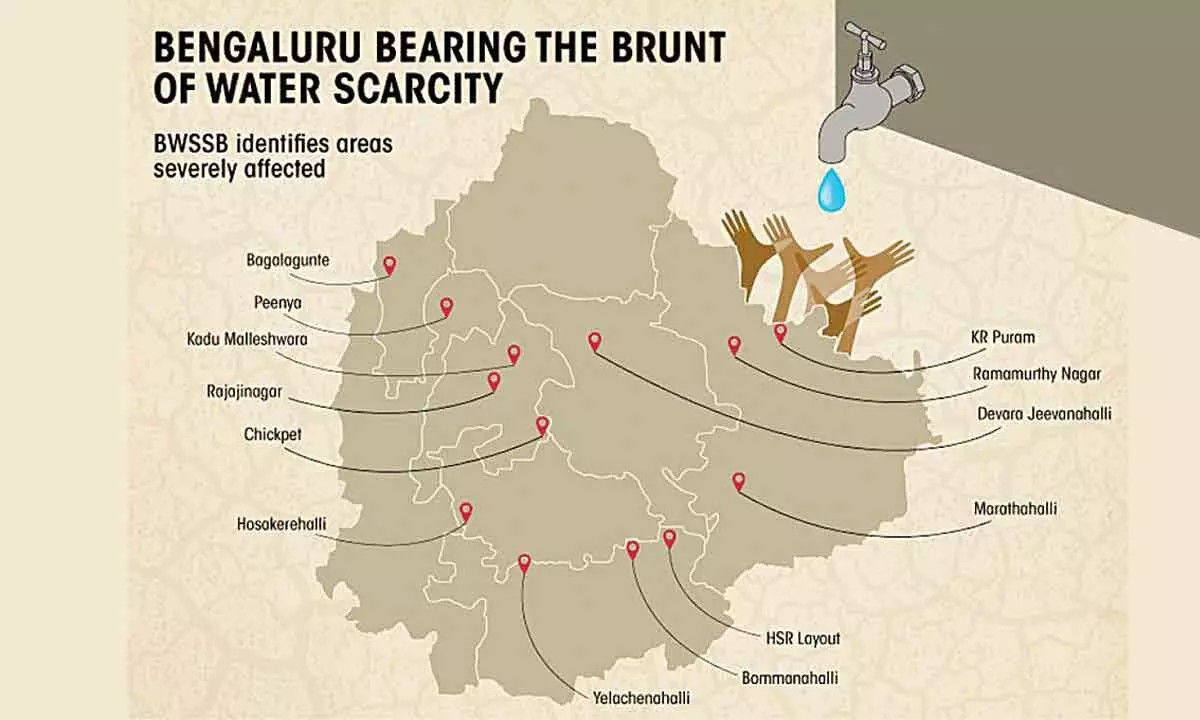

image for illustrative purpose

Policy makers therefore must be held accountable for allowing such an unchecked growth in population. Instead of expanding in all directions, Bengaluru could have gone in for city diversification – encouraging neighbouring towns to take on the population influx

Several years back, I read a very interesting article in the Times magazine “What’s it’s like to live through Cape Town’s massive water crisis.” Fearing that the city will run dry in the months to come, South Africa’s coastal paradise became the first city to not only sound a warning but to explain how dreadful it will be when taps run dry and the search for ground water to meet the daily needs also run out.

In the last few weeks, a number of articles on the severe water crisis that Bengaluru is faced with, reported about how residents of high rise buildings were compelled to use toilets in the neighbouring malls, drawing parallel with Cape Town’s dystopian scenario.

One article in particular in the Indian Express “When the taps run dry” (March 19) showed how the city of lakes (as it was once known) became an urban concrete jungle, a victim of economic growth.

Seema Mundoli from Azim Premji University in her thought-provoking article, actually prompted the readers to reflect on the three Rs – our relationship, our rights and our responsibilities – on how the educated have allowed the dreams to fade away so fast.

This is where I think it has become important to compare Bengaluru’s water crisis with Punjab’s alarming depletion of ground water. While the water guzzling paddy cultivation is being cited as the major reason behind rapid groundwater depletion, with more than 109 blocks of the 138 development blocks already falling in the dark zone (where the rate of extraction is higher than the rate of replenishment), the search for water has made farmers install submersible pumps to go still deeper, and in many cases source it directly from the aquifers. Numerous studies have shown that Punjab’s ground water will run out soon, with some even predicting that the groundwater will last not for more than 17 years.

In Punjab, despite crop diversification being suggested for several decades now, the area under paddy has actually grown. This year, the State recorded the highest acreage under paddy and also the highest yield. Although paddy is known to require more than 5,000-litres of water (it varies from state to state) to produce one kg of rice, Punjab remains the biggest contributor of rice to the Central pool. Therefore it plays a significant part in ensuring food security. Still, it is because the Centre/State governments haven’t come up with an economically strong alternative to paddy, crop diversification hasn’t yet taken roots.

Crop diversification has been talked about for long. And it makes me wonder if crop diversification can be a solution for Punjab, why can’t it be ‘city diversification’ in the case of Bengaluru?

Well, before you ask me what I mean by ‘city diversification’, let me explain. Given the carrying capacity of the metropolis, the city is now bursting at the seams. From 8.7 million in 2011, the population had grown to an estimated 12.5 million by 2021 and should be close to 15 million by now. Policy makers therefore must be held accountable for allowing such an unchecked growth in population. Instead of expanding in all directions, Bengaluru could have gone in for city diversification – encouraging neighbouring towns to take on the population influx.

In any case, sustainable development of ‘cities and communities’ falls under SDG 11, and this is also linked to SDG 8 which talks of ‘decent work and economic growth’. Making ‘cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable’ is one of the tasks laid out by SDG 11. Restricting urban sprawl to ensure sustainability should have been the task of City Municipal Councils.

Measures like making tap aerators compulsory now as a fire-fighting exercise to reduce water wastage is an afterthought. Such ad hoc decisions cannot address a crisis that is pointing to a grim future. At the same time, the way in which the networks of lakes and water bodies have been lost to urbanization is seen as something inevitable. On the contrary, this is nothing but an abuse of administrative power that allowed the lakes to be gobbled up by builders.

Many lakes have become the dumping ground for huge garbage and waste that the city throws up every day. Despite a people’s movement to rejuvenate lakes, the administration seems to be in a slumber. Even now, all eyes are on setting up a housing complex in 24 acres of Junnasandra lake in eastern part of the city that has dried up. Around the IT hub, Halanayakanahalli lake is a dumping ground for all kinds of debris and garbage. As someone said, many lakes have become perennial – with waste and debris.

Associated with increasing paddy cultivation, Punjab farmers are also blamed for stubble burning. These farm fires collectively burn about seven to eight million tonnes of paddy residues every year. While incentives have been given for crop residue management machines, farmers are also under the scanner for putting the plant biomass to fire. Coercive measures like FIR against erring farmers, penalties, and certain other steps like red entries in revenue records and restricting the supply of subsidized inputs have been imposed.

That makes me wonder why can’t FIRs be filed against the administrative officials and the real estate companies that have taken possession of lands that once formed the lakes and water bodies. Why should there be double standards when it comes to penalizing farmers and city dwellers for environmental lapses? Why city dwellers should be treated with velvet gloves while all kinds of punitive actions are taken against farmers?

For every economic activity there is always a talk of public-private partnership. But when it comes to addressing massive problems like the water crisis, I don’t see the private sector willing to join hands in a collaborative effort. Interestingly, a Facebook post suggesting that Rs. 240 crore worth of share that N.R. Narayana Murthy gifted to his four-month-old grandson could have been put to better use if such donations could be diverted for a much acute water crisis that affects the city’s future.

It evoked an angry response from some readers who believe in the dictum ‘privatisation of profits, socialisation of costs’. Whatever be your opinion, it certainly remains a collective responsibility of the public and private sector to stand up at times of an extraordinary crisis that the city they live in is engulfed in.

Jared Diamond, the Pulitzer-winning author, had in his book ‘Collapse’ looked at several societies that have collapsed as a result of misusing their natural resources. He talks of the collapse of Angkor Wat in Cambodia and Mohenjo-daro, now in Pakistan, as the two examples of flourishing settlements that subsequently were abandoned. Let us hope that the modern societies do not repeat the failures, and the gross mismanagement of the natural resources does not lead to collapse of growing cities and that too in the 21st century.

(The author is a noted food policy analyst and an expert on issues related to the agriculture sector. He writes on food, agriculture and hunger)